Understanding the state of the atmosphere starts with good observations, and one of the most important tools we have is the weather balloon. Twice a day, at 00 and 12 UTC, around 1000 sites worldwide launch radiosondes (GPS-equipped radio-transmitting instruments) to gather temperature, moisture, pressure, and wind information we use for atmospheric sounding interpretation. These soundings form the backbone of modern forecasting, supporting tools like the ones we build at Wet Dog Weather.

What is a Radiosonde

The instrument attached to each balloon is called a rawinsonde or radiosonde. These devices are small, lightweight packages made mostly of styrofoam with an internal control board. Research sondes can weigh as little as 90 grams. Typical National Weather Service radiosondes weigh between 250 and 500 grams and are considered safe for aviation. Their launch times and locations are still communicated to air traffic controllers as a precaution.

The biodegradable latex balloons carrying these instruments rise until they burst. Most reach the tropopause at roughly 10-12 km, after which the internal pressure overwhelms the balloon. Some sondes even make surprise returns. One launched by the University of Virginia’s Atmosphere and Weather Lab was recovered more than 200 miles away after landing in a tree on the East Coast.

Atmospheric Sounding Interpretation on a Skew-T Diagram

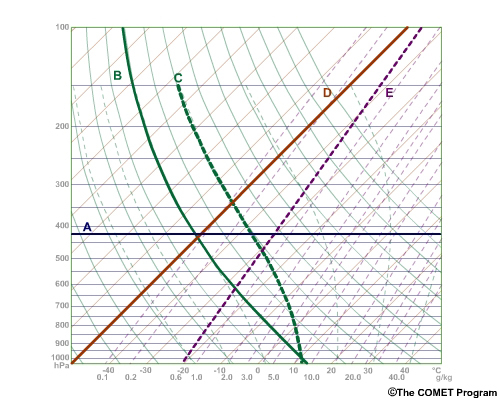

To make sense of the data radiosondes collect, meteorologists plot temperature and dewpoint on a skew-T log-P thermodynamic diagram. Atmospheric sounding interpretation begins here, where pressure, temperature, moisture, and parcel behavior can be viewed together.

Let’s look at the core elements:

A) Isobars: lines of constant pressure

B) Dry adiabats

C) Moist adiabats

D) Isotherms: lines of constant temperature

E) Mixing ratio lines

Pressure decreases exponentially with height, so a logarithmic scale expands the lower atmosphere where most weather occurs. The isotherms are skewed to make calculations and parcel tracing easier.

Adiabats and Parcel Behavior

The adiabats show how a parcel of air warms or cools as it moves vertically. The dry adiabatic lapse rate is about 10 degrees Celsius per kilometer and applies to unsaturated air. Once a parcel becomes saturated, condensation releases latent heat, which slows the cooling rate. This produces the moist adiabatic lapse rate of roughly 4 to 9 degrees Celsius per kilometer.

In most cases, a rising parcel follows a dry adiabat until it reaches its condensation level. After that point, it continues along a moist adiabat. Descending air always warms dry adiabatically due to compression.

Mixing Ratio Lines and Moisture Content

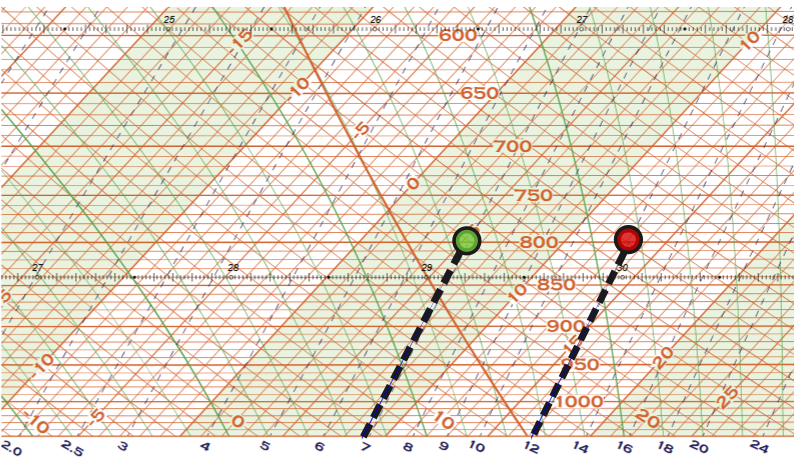

Mixing ratio lines help determine how much water vapor an air parcel contains. The units are grams of vapor per kilogram of air. Using dewpoint and temperature at a given pressure level, we can compute relative humidity.

For example, at 800 hPa, a parcel with a dewpoint (shown in green) of 5.5°C and a temperature (shown in red) of 13°C contains 7 g/kg of water vapor and could contain up to 12 g/kg. That gives a relative humidity near 58 percent. Dewpoint alone reveals the actual moisture content, which is why it is essential in atmospheric sounding interpretation.

Key Levels in Atmospheric Sounding Interpretation

Soundings allow us to identify several important atmospheric thresholds.

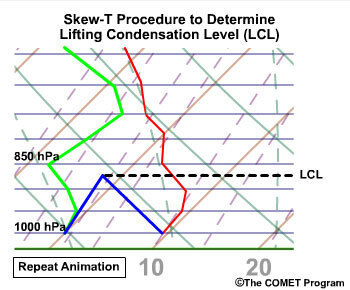

Lifting Condensation Level (LCL)

The LCL is the height at which a parcel becomes saturated when lifted mechanically, such as over a mountain range.

To determine the LCL, follow the mixing ratio line from the surface dewpoint until it intersects with the dry adiabat that begins at the surface temperature.

In this example, the LCL is near 860 hPa or about 1.4 km above the surface.

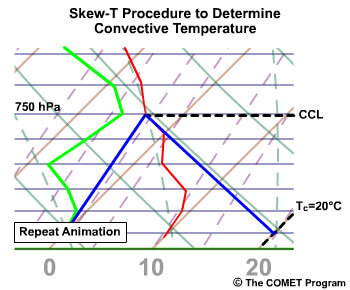

Convective Condensation Level (CCL)

The CCL is the height where convectively rising thermals first reach saturation. These often form the bases of cumulus clouds on warm, sunny days.

To find the CCL, follow the surface mixing ratio until it intersects the environmental temperature curve aloft.

The dry adiabat traced downward from the CCL yields the convective temperature, the surface temperature needed to initiate convective cloud formation.

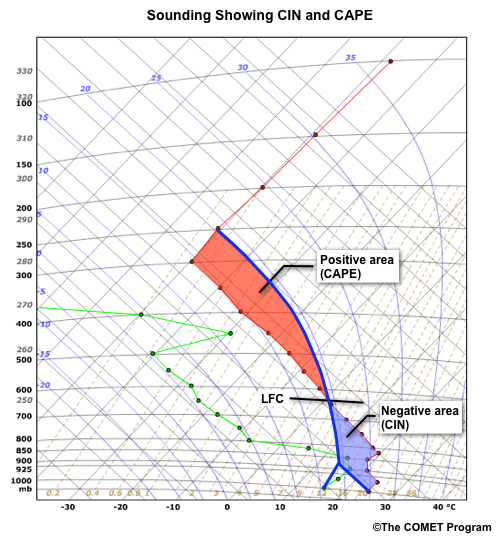

Level of Free Convection (LFC)

The LFC marks the point where a lifted parcel becomes warmer than its surroundings and begins to rise freely. To determine the LFC, we start at the LCL and rise up the moist adiabat. This transition is driven by latent heat released during condensation.

Equilibrium level (EL)

The EL is the altitude where a rising parcel becomes neutrally buoyant again. On highly unstable days, the EL can extend to more than 22 km. Pilots rely on this information to avoid deep, turbulent columns of rising air.

The convective available potential energy (CAPE) represents the area on the Skew-T where a parcel’s ascent along the moist adiabat exceeds the environmental temperature. This area corresponds to potential storm intensity. The convective inhibition (CIN), on the other hand, is the stable layer that initially prevents parcels from rising.

Why Atmospheric Sounding Interpretation Still Matters

Atmospheric sounding interpretation remains a foundational skill across meteorology. Forecasters rely on soundings to anticipate storm development hours before clouds appear. Pilots use them to evaluate turbulence and icing risks along their routes. Storm chasers watch CAPE and CIN trends to determine whether explosive convection is likely. Numerical weather models depend on these observations for validation and better initialization.

Whether the goal is safety, science, or situational awareness, sounding data offers a vertical snapshot of the atmosphere that no other observing system can fully replace. As long as we need to see inside the sky rather than just across it, atmospheric sounding interpretation will remain one of our most valuable tools.

An archive of sounding data is freely available from the University of Wyoming Sounding page.